PewDiePie Isn’t A Monster; He’s Someone You Know

This essay is a guest post from the Deputy Editor at Screener, a site for critical writing on television and streaming and the new home of Television Without Pity.

PewDiePie at Barnes & Noble Union Square on Oct. 29, 2015, in New York City.

John Lamparski / Getty Images

This week, Disney dropped Swedish YouTube star Felix “PewDiePie” Kjellberg after the Wall Street Journal raised questions about anti-Semitic messages in several of his videos. YouTube followed suit shortly afterward, canceling the upcoming second season of his web series, Scare PewDiePie. Some of his more line-crossing content has been deleted, and he’s no longer a “Google Preferred” producer at YouTube — although, as Patricia Hernandez at Kotaku explained, Kjellberg still makes advertising profit from his work.

For those who don’t enjoy them, Kjellberg’s videos, in which he performs running commentary while playing video games, are nails on a chalkboard even when they don’t include Nazi references. And so it’s not surprising that, outside the video game/vlogger community, the online reaction to his fall from grace has been almost uniformly a smug satisfaction.

The fact that this was framed as a full-scale investigation and major story for the Journal should be a reminder of both the outsize paychecks digital video personalities draw (Forbes estimated Kjellberg’s earnings at $15 million in 2016, making him the highest-paid star on YouTube) and the vast, devoted fan bases that enable them. As of December 2016, Kjellberg had an astonishing 50 million YouTube subscribers.

So that’s one story we could tell, about how the tech, money, and celebrity spheres we’re familiar with all converged on the most hot-button issue of 2017: the rise of white nationalism and fascism in America. It’s a slam dunk. But it’s not the real story.

The real story with PewDiePie is not that somebody you’re preconditioned to hate — whether out of personal distaste for his combination of Euro-DJ obliviousness and shrieking energy, or because you dismiss his industry at large, or because you’re incredulous that anybody could make this much money doing basically nothing — got his just deserts. That’s missing the point, because PewDiePie himself is beside the point. He is one of 50 million-and-one drops in an ocean, caught in a tide toward a nasty shore.

PewDiePie is one of 50 million-and-one drops in an ocean, caught in a tide toward a nasty shore.

The online alt-right is built on lulz, and on an insulated privilege enjoyed by people without any personal context for or historical understanding of the things their privilege lets them say. Rewriting Felix Kjellberg’s history to make him a monster — pulled along by the gravity of recent high-impact cautionary tales like those of Milo Yiannopolous and Richard Spencer — is investigative laziness that obscures a much more important fact: that “edgelords,” the boys and men who group together online for the explicit proliferation of hate speech and misogyny, will almost inevitably keep pushing the line until they end up in a truly dark place.

Because PewDiePie’s relationship to his following, like that of Milo to his own fans, is both a reciprocal system of validation and a male personality cult, we don't diagnose it as anything out of the ordinary: We take it at face value, because “men are men.” We can demonize “them” (the ones who go too far) as an idea, continue to ignore them in reality, and then act shocked when their need for attention finally intersects with their ability to make themselves heard.

This isn’t about being right. Of course joke-racists, trolls, and budding fascists are wrong; of course they’re out of control, abetted by corporations who provide them with platforms to organize and speak. This is about understanding what lies beneath this dark side of the internet, and how to stop it.

Kjellberg is not the first or only video creator of his type, but his fingerprints are everywhere. The glut of “Let’s Play” videos and other game-tangential content that makes up the majority of high-subscriber YouTube content bears his marks, his idioms, his pressured speech. By luck and serendipity, his effect on a predominant emerging media format of the 21st century is permanent, generating tropes and formats and standards for expression as far-reaching as his fame. If YouTubing is an art, he’s an accidental Picasso.

But most of the people talking about Kjellberg right now aren’t actually that familiar with him. Humans tend to overestimate how common our own positions and interests actually are, a phenomenon called false-consensus bias. It explains why your relatives are constantly shocked by things on Facebook; it explains in large part why both the left and right are shocked by the reactions to Presidents Trump and Obama. It also explains why Felix Kjellberg is such an easy blank canvas for our essays and thinkpieces: because he matters most to young people whose ideas and obsessions still aren&039;t taken seriously by mainstream discourse.

Among 13-to-18-year-olds, Variety reported in 2014, PewDiePie is more recognizable than Jennifer Lawrence. If you find that impossible to believe, you are coming upon an understanding of false-consensus bias. Kids on screens — who largely ignore the entertainment and news and culture that you deem important, the world as the rest of us understand it — are building their own world: building the future. Fifty million of them. And PewDiePie’s fans, like it or not, are getting something real from him.

“Many people see me as a friend they can chill with for 15 minutes a day,” Kjellberg explained in 2014. “The loneliness in front of the computer screens brings us together. But I never set out to be a role model; I just want to invite them to come over to my place.”

Given that attachment, that not-quite-even-simulated intimacy, there’s nothing quite so disappointing as a YouTube personality letting slip an unconscious prejudice or unattractive attitude. In the earliest weeks of 2017, Kjellberg’s unreconstructed understanding of social and political dynamics led, as it often does, to disaster.

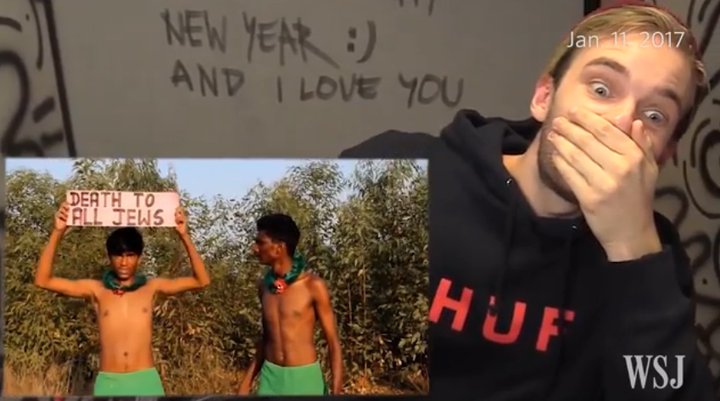

First, The Sun isolated audio from a video in which Kjellberg uses a racial slur during a particularly celebratory moment. A few days later, a steadily increasing propensity for referencing Nazis, Hitler, and anti-Semitic topics – the Wall Street Journal counts nine – exploded, in a sketch in which Kjellberg hired a pair of men in India to hoist a banner calling for the death of all Jews (a request that Kjellberg maintains he never thought they would carry out).

Kjellberg has never been a particularly enlightened individual. His distracted, screeching patter has always contained a few too many “bitches”; his insistence on addressing his followers as “bros” is part and parcel of the unrealistically male-focused view that gaming culture has of its own demographics (that false-consensus bias again). And as an influencer, that means Kjellberg adds to it by abetting it: He is both a creature of, and unavoidably a thought leader in, a nominally masculine industry and culture undergoing extreme identity crisis.

PewDiePie / WSJ

Reddit “ironists,” imageboard Pepe posters, and all the other uncreative online shock jocks are born of a culture that is insulated from real life. Hitler jokes and rape jokes alike come originally from naivete, and eventually harden into belief: Witness so many standup comics caught with their pants down, who then get so hurt by the backlash that they double down, becoming vicious. Projecting our cultural shadow onto their Other — we, the good people, searching out and stomping out those who are secretly not good — keeps us from seeing how these communities start, grow, and feed on our dismissal.

This isn’t an argument against political correctness, which is a vile concept created by conservatism, and it’s not a call to sympathy for the internet trolls of the world. But sunlight is the best disinfectant, and what you can’t see — or what you refuse to see — you can’t fix. Hiding from the ugliest parts of our own culture is putting them in a position to do the most damage.

We’re conditioned to distance ourselves from Reddit dorks, anime-avatar trolls, and suddenly Nazi-identifying furries, and so they stay invisible — until they aren’t. They become collectives, at which point it feels like they came from nothing. But they came from somewhere: boredom, loneliness, and the universal feeling (which most of us are lucky enough to overcome in childhood) of being the protagonist of the universe, who is mistreated despite doing one’s best.

To these boys, rape and Anne Frank are equally ghost stories, equally a path to extremity. The thing is that this breed of deeply aggrieved male nerd will always talk louder, talk over each other, talk over women. Nerds scream because they don’t feel heard. That’s the only reason anyone ever does.

The joke hate eventually evolves into real hate.

It&039;s just a short step from like-minded victim-heroes linking up to edgelords radicalizing each other, just like Men’s Rights Activists, or creepy Pick-Up Artists: Nobody else gets their embattled perspective, their need for validation, their need for help. In fact, they’re vilified for it. And so they urge one another on, and because all humor is based on seeds of discomfort, and seeds can eventually bloom, the joke hate eventually evolves into real hate.

Imagine the acceptable level of hatred in humor, even just a couple of decades ago, from blackface to spousal abuse and “Spanish Fly” — and how it might have evolved, without pushback from society at large to stop it. Imagine that the people making these so-called jokes today exist in a world, as far as they understand or emotionally value it, that is full of people urging them on.

Because we overlook these folks as they travel from A to B, we assume that A equals B; they never “changed,” they just got their covers pulled. We looked away, in reality, just long enough for the change to occur outside our peripheral vision. The reality is that they were begging for limits, and we didn&039;t offer them, because they&039;re too gross to look at. Drawing a self-comforting line between “Reddit dorks” over here and “monsters” over there does nothing to stop them, much less help them. It only serves the rest of us.

Suhaimi Abdullah / Getty Images

We got so used to invoking Godwin’s Law (the idea that every internet discussion will eventually reach the point of comparing something to Hitler or Nazis) that we internalized it, and can’t hear certain terms anymore because they’re too big to let in the door. When you are saying something that big, taking it that far, and still don’t feel heard, you get louder and louder, doubling down every time — and then to still feel invisible?

Then, too, people like Felix Kjellberg and Milo Yiannopoulos are not American, which adds an extra layer of noise between them and their understanding the visceral reality of what they’re saying. The poisonous aspect of that is that it covers their American followers like a blanket of safety: They make their “jokes” from one more hurdle down the line, normalizing it, and dragging their fans along.

Imagine how easy it would be to idolize someone who so regularly can be counted upon to reframe your personal Overton Window — the category of what you think is unthinkable — to include things you wouldn’t have said six months ago, every six months. It’s a wonderful feeling, of liberation and transgression, and it never ends: What gave you a thrill now sounds commonplace, everyone is saying it, everyone has normalized it, and we need to move on to something else. Something worse, or else nobody will pay attention. This reciprocating discourse provides incredible validation, teaching that the worst thing a guy can think doesn’t make him a terrible person, but a hero.

This group-therapy strategy also means granting one another a form of permission: We overlook the degree to which men are constantly checking in with each other, or the “alpha” in any given situation, to see where the line is — c.f. Trump telling Billy Bush “they” let you do anything — and when neither side of that conversation has a sense of authority, it becomes a self-reinforcing system of okays and consensus.

The wobble-and-fall, then, is a predictable arc: It’s the hyperactive child at dinner who gets a laugh, then repeats the joke enough times that he’s banned from the table. Only in Kjellberg’s case, the attention he was getting wasn’t from adults, hiding smiles behind their hands, but from the base he’d spent five years cultivating, pleasing, and urging ever onward in turn.

Questioning this basic framework — of collaborative ideology, of the complex cues boys and men use to inform and police their own and others’ behavior — is breaking the rules of Boy Club. It&039;s impossible to ask the question without coming up against male fragility, against the #NotAllMen defense of masculinity: “How dare you say I’m following the leader?”

With a celebrity like Kjellberg, it also invokes the idea that, if being a “fan” is part of your identity, any questioning of him is an indictment of you on at least two levels: both as a heroic independent thinker, and as a man with refined enough tastes to like the thing that you like. An exploration of your culture, whether that’s video games or YouTubers or white supremacy, is absolutely an attack on you, from an angle you’re no more likely to see than you are the back of your own head. Because, like any question of privilege, its effect is existential, practically Lovecraftian: You think the world is like this, but really it’s like that, and our brains are not capable of processing that way.

Every edgelord and burgeoning fascist fancies himself a Neo, opening his eyes to the secret truth.

Quelle: <a href="PewDiePie Isn’t A Monster; He’s Someone You Know“>BuzzFeed