In early December, Facebook published a blog post summing up the company’s breakthroughs and challenges in image and speech recognition. Halfway down the page in a section explaining how Facebook’s computers are “quickly getting better” at identifying the objects in pictures and videos, the company embedded an animated GIF showing off its AI analysis of a photograph taken at a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest.

It was an odd choice of illustration for a blog post touting Facebook’s machine learning advancements. Just days before, rumors had begun circulating that authorities had been using Facebook to identify Dakota Access pipeline protesters in North Dakota. And a few weeks prior to that, the ACLU had released a report revealing that the company's API had been used in 2014 to track protesters in Ferguson.

The GIF circulated on Twitter as an example of unsettling, tone-deaf PR from one of the world’s most powerful tech companies. A few hours after I tweeted that the image was “unnerving,” a Facebook product manager and business lead to the CTO contacted me, somewhat bewildered. “Curious to know why you think so. It was a frequently shared and meaningful image from this year that AI fails to interpret,” he replied. A few minutes later, after concerned tweets from others piled up, he wrote back again, “based on this feedback I think we didn&039;t put enough of that context into the post. Appreciate feedback.” The image was removed an hour later.

That Facebook failed to see how such an emotionally charged image might trigger deeply held anxieties about the social network’s power and influence was telling. But that the company’s users objected loudly enough to force a correction highlighted a fundamental shift in how tech’s biggest companies are held to account this year.

For years, Silicon Valley’s biggest platforms have thrown their collective hands in the air amid controversies and declared, “We’re just a technology company.” This excuse, along with “We’re only the platform” is a handy absolution for the unexpected consequences of their creations. Facebook used the excuse to shrug off fake news concerns. Airbnb invoked it to downplay reports of racial discrimination on its platform. Twitter hid behind platform neutrality for years even as it was overrun with racist and sexist trolls. Uber even used the tech company argument in a European court to avoid having to comply with national transportation laws.

But in 2016, Big Tech’s well-practiced excuse became less effective. The idea that their enormous and deeply influential platforms are merely a morally and politically neutral piece of the internet’s infrastructure — much like an ISP or a set of phone lines — that should remain open, free, and unmediated simply no longer makes ethical or logical sense.

In 2016, more than any year before it, our world was shaped by the internet. It’s where Donald Trump subverted the media and controlled the news cycle. Where minorities, activists, and politicians from both sides of the aisle protested Trump&039;s candidacy daily. And where emergent, swarming online hate groups (including but not limited to the so-called alt-right) developed a loud counterculture to combat liberalism. Startups like Uber and Airbnb didn&039;t just help us navigate the physical world, but were revealed as unwitting vectors of bigotry and misogyny. This year, the internet and its attendant controversies and intractable problems weren’t just a sideshow, but a direct reflection of who we are, and so the decisions made by the companies and platforms that rank among the web’s most prominent businesses became harder to ignore.

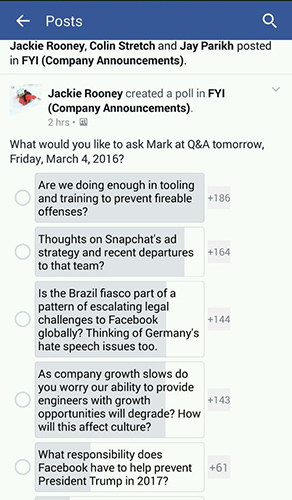

A leaked Facebook internal post obtained by Gizmodo about Facebook&039;s responsibility to prevent a Trump presidency.

Gizmodo / Via gizmodo.com

This spring, Facebook dismissed the notion that it has any institutional biases when Gizmodo published leaked internal communications that suggested employees were floating ways in which the platform could be used to stop Trump’s bid to the White House. Similarly, when Gizmodo reported that the company’s Trending Topics team suppressed conservative news, the company denounced the actions and fired the team: Such bias, Facebook said, was unacceptable for a pure technology company where engineers build agnostic tools and blind platforms with the simple desire to connect the world.

And post-election, in response to claims that it allowed political misinformation to spread unchecked, Facebook argued that it was not a media company but a technology company. No matter that it pulled in more than $6 billion in advertising revenue in just the second quarter of 2016. Facebook claimed it was a “crazy idea” that the very same platform that has unmatched influence over its billion users’ spending habits also had influence over those same users’ political decisions. (The company has since walked back its excuse and has begun to find ways to partner with fact checkers and even flag demonstrably false news and misinformation on the platform. A week ago, Zuckerberg changed his definitions, calling Facebook “a new kind of platform.” He argued that it was “not a traditional technology company. It’s not a traditional media company. You know, we build technology and we feel responsible for how it’s used.”)

Also in 2016, Facebook rolled out a live video tool that gave nearly 2 billion people the ability to broadcast from their phones in real time. Live gave us an exploding watermelon and Star Wars Mom, but it also gave us the last minutes of Philando Castile’s life and the ensuing protests. Just as the Castile post started to go viral, it vanished from the network. It was restored, but not before raising urgent questions as to how Facebook would or wouldn&039;t censor newsworthy content (many of which went unanswered). Facebook bet big on building the technology to become the internet’s primary destination for live video but appeared unwilling to reckon with its power to bear witness to the worst that the world has to offer. It blamed the Castile incident on a technical glitch.

Both Twitter and Reddit repeatedly suggested that they are global town squares and open public forums and thus ought not to be moderated except in extreme cases. Like Facebook, they refused to see themselves as media companies or publishing platforms, despite being powerful tools for news, publishing, and politicians (this year Twitter reclassified itself in the Apple App Store as “news” instead of “social networking”). And then they watched as their platforms were overrun with trolls. Tools for free speech were used by nefarious actors to suppress the speech of others while little was done by the companies for fear of creating precedent for aggressive censorship. Again, this isn’t new: For the last decade, the crash of utopianism against the rocks of human reality has arguably been the defining story of the internet.

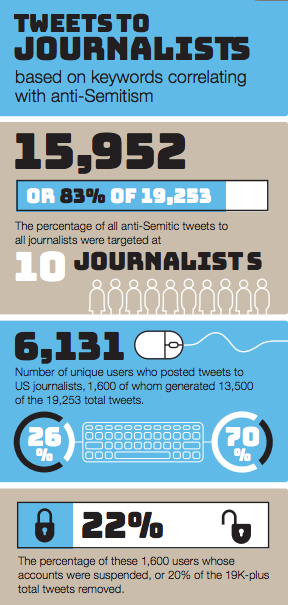

But in 2016, the consequences of these missteps became realer. Jewish journalists saw their pictures photoshopped into gas chambers and circulated around Twitter and across the internet. A Reddit community (r/The_Donald) dedicated to Donald Trump’s candidacy allegedly harassed other communities and led a campaign to take over the front page of the site — one of the biggest on the internet. Donald Trump rewarded them by appearing on the site for an “Ask Me Anything” Q&A. Trolls waged misinformation campaigns to try to disenfranchise black and Latino voters supporting Hillary Clinton. Twitter was a free megaphone for the now-president-elect to attack the press, disseminate misinformation, and even target private citizens who challenged him, each of his tweets setting off a wave of targeted hate, threats, and abuse toward their subjects.

ADL

But users and observers fought back. The Anti-Defamation League assembled a Twitter harassment task force to combat the rise of anti-Semitism on the platform. Leslie Jones responded to her targeted harassment by very publicly quitting Twitter, which led to the permanent suspension of one of its master trolls. Former employees spoke out against Twitter’s decade-long struggle to protect its users from abuse. CEO Jack Dorsey faced pressure from journalists and advocates for not making abuse prevention a priority. Reddit has begun steps to keep r/The_Donald from overwhelming other communities on the site. Twitter rolled out a set of new abuse tools and internal user support practices. It began a series of crackdowns on alt-right trolls, and it publicly vowed to stay vigilant. Enforcement remains inconsistent and opaque, but the company now operates under the watchful scrutiny of journalists and loud and critical users.

It’s not just the online platforms. Startups like Uber and Airbnb, which are powered by tech but operate almost exclusively in the physical world, drew ire for invoking the “tech company” excuse. This year Uber argued in European court that it is a digital platform, not a taxi or transportation company. It argued this despite its very public ambitions to reshape cities and change the nature of car ownership. It argued this despite the fact that it now builds autonomous vehicles that move real people on real city streets and despite the fact that it is arguably the largest dispatch transportation company in the world, with vehicles in over 300 cities and six continents and an estimated valuation of around $68 billion. It argued that it is just a technology company despite the fact that downloading and hailing and stepping into a cab brings with it far more visceral — and potentially serious — risks than that of a simple digital platform.

Uber’s argument largely fell flat in 2016. In Europe, the company faces lawsuits from taxi associations and protests from drivers for undermining transportation companies across the continent. Continuing reports of sexual assault and driver misconduct led to lawsuits and proposed legislation and transparency from governments in places like New York City. Just this month, Uber’s self-driving technology was pulled off streets in San Francisco by the DMV for being deployed too early.

After initial reports of racial discrimination from people using its home rental platform, Airbnb proffered a flaccid defense. “We prohibit content that promotes discrimination, bigotry, racism, hatred, harassment or harm against any individual or group,” the company said in May. But as reports of racial profiling on Airbnb continued to surface, the company was forced to address the issue in earnest. In a moment of candor, co-founder Brian Chesky suggested that the company’s creators hadn’t anticipated the potential for abuse. “We’re also realizing when we designed the platform, Joe, Nate, and I, three white guys, there’s a lot of things we didn’t think about when we designed this platform. And so there’s a lot of steps that we need to re-evaluate,” he said in July.

In some ways, Chesky’s comments about the unintended consequences of platform design speak to the frustration we, the users, feel when we’re faced with the “We’re just a technology company” excuse. The unspoken corollary to this argument seems to be “Hey, we&039;re just a platform, we&039;re not responsible, nor could we ever be liable for the design choices that guide and enable our users.”

But as we saw this year, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Facebook’s not just the place where you go to play Farmville and like pictures of your friend’s babies — it’s a filter-bubbled window through which more than a billion people view the world. Twitter isn’t a global town square or park, it’s the world’s most important newswire and, for some, a wildly effective way to quickly communicate with a massive audience. Uber isn’t an app, it’s a global transportation company that can, and in fact intends to, forever reshape the way humans get from point A to point B. Airbnb isn’t a vacation rental site, it’s a new vision of home ownership and travel accommodations.

For years, Silicon Valley’s biggest companies have been telling us they plan to reshape our lives online and off. But 2016 was the year that we really started taking those claims seriously. And now, in a world where Donald Trump can ascend to the highest office buoyed by fake news and 5 a.m. tweetstorms, and platforms like Uber and Airbnb have shown themselves vulnerable to the whims of some prejudiced users, there’s an emerging expectation of accountability for the platforms that are reshaping our world daily.

In other words, trotting out the “But we’re just a digital platform” excuse as a quick and easy abdication of responsibility for the perhaps unforeseen — but maybe also inevitable — consequences of Big Tech&039;s various creations is fast becoming a nonstarter. Until recently, Facebook’s unofficial engineering motto was “Move fast and break things” — a reference to tech’s once-guiding ethos of being more nimble than the establishment. “Move fast and break things” works great with code and software, but 2016’s enduring lesson for tech has proven that when it comes to the internet’s most powerful, ubiquitous platforms, this kind of thinking isn’t just logically fraught, it’s dangerous — particularly when real human beings and the public interest are along for the ride.

Quelle: <a href="2016: The Year We Stopped Listening To Big Tech’s Favorite Excuse“>BuzzFeed

Published by