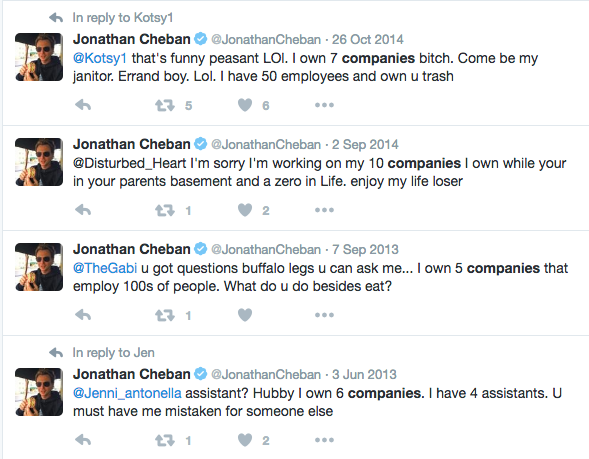

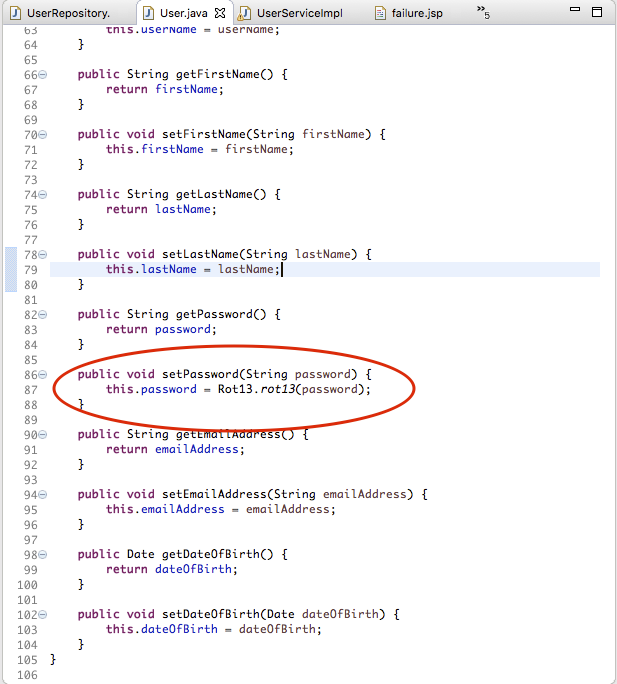

A very, very small quadcopter, one inch in diameter can carry a one- or two-gram shaped charge. You can order them from a drone manufacturer in China. You can program the code to say: “Here are thousands of photographs of the kinds of things I want to target.” A one-gram shaped charge can punch a hole in nine millimeters of steel, so presumably you can also punch a hole in someone’s head. You can fit about three million of those in a semi-tractor-trailer. You can drive up I-95 with three trucks and have 10 million weapons attacking New York City. They don’t have to be very effective, only 5 or 10% of them have to find the target.

There will be manufacturers producing millions of these weapons that people will be able to buy just like you can buy guns now, except millions of guns don’t matter unless you have a million soldiers. You need only three guys to write the program and launch them. So you can just imagine that in many parts of the world humans will be hunted. They will be cowering underground in shelters and devising techniques so that they don’t get detected. This is the ever-present cloud of lethal autonomous weapons.

They could be here in two to three years.

— Stuart Russell, professor of computer science and engineering at the University of California Berkeley

Mary Wareham laughs a lot. It usually sounds the same regardless of the circumstance — like a mirthful giggle the blonde New Zealander can’t suppress — but it bubbles up at the most varied moments. Wareham laughs when things are funny, she laughs when things are awkward, she laughs when she disagrees with you. And she laughs when things are truly unpleasant, like when you’re talking to her about how humanity might soon be annihilated by killer robots and the world is doing nothing to stop it.

One afternoon this spring at the United Nations in Geneva, I sat behind Wareham in a large wood-paneled, beige-carpeted assembly room that hosted the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), a group of 121 countries that have signed the agreement to restrict weapons that “are considered to cause unnecessary or unjustifiable suffering to combatants or to affect civilians indiscriminately”— in other words, weapons humanity deems too cruel to use in war.

The UN moves at a glacial pace, but the CCW is even worse. There’s no vote at the end of meetings; instead, every contracting party needs to agree in order to get anything done. (Its last and only successful prohibitive weapons ban was in 1995.) It was the start of five days of meetings to discuss lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS): weapons that have the ability to independently select and engage targets, i.e., machines that can make the decision to kill humans, i.e., killer robots. The world slept through the advent of drone attacks. When it came to LAWS would we do the same?

Yet it’s important to get one thing clear: This isn't a conversation about drones. By now, drone warfare has been normalized — at least 10 countries have them. Self-driving cars are tested in fleets. Twenty years ago, a computer beat Garry Kasparov at chess and, more recently, another taught itself how to beat humans at Go, a Chinese game of strategy that doesn’t rely as much on patterns and probability. In July, the Dallas police department sent a robot strapped with explosives to kill an active shooter following an attack on police officers during a protest.

But with LAWS, unlike the Dallas robot, the human sets the parameters of the attack without actually knowing the specific target. The weapon goes out, looks for anything within those parameters, hones in, and detonates. Examples that don’t sound entirely shit-your-pants-terrifying are things like all enemy ships in the South China Sea, all military radars in X country, all enemy tanks on the plains of Europe. But scale it up, add non-state actors, and you can envision strange permutations: all power stations, all schools, all hospitals, all fighting-age males carrying weapons, all fighting-age males wearing baseball caps, those with brown hair. Use your imagination.

While this sounds like the kind of horror you pay to see in theaters, killer robots will shortly be arriving at your front door for free courtesy of Russia, China, or the US, all of which are racing to develop them. “There are really no technological breakthroughs that are required,” Russell, the computer science professor, told me. “Every one of the component technology is available in some form commercially … It’s really a matter of just how much resources are invested in it.”

LAWS are generally broken down into three categories. Most simply, there&039;s humans in the loop — where the machine performs the task under human supervision, arriving at the target and waiting for permission to fire. Humans on the loop — where the machine gets to the place and takes out the target, but the human can override the system. And then, humans out of the loop — where the human releases the machine to perform a task and that’s it — no supervision, no recall, no stop function. The debate happening at the UN is which of these to preemptively ban, if any at all.

“I know that this is a finite campaign — the world’s going to change, very quickly, very soon, and we need to be ready for that.”

Wareham, the advocacy director of the Human Rights Watch arms division, is the coordinator of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, a coalition of 61 international NGOs, 12 of which had sent delegations to the CCW. Unlike drones, which entered the battlefield as surveillance technology and were weaponized later, the campaign is trying to ban LAWS before they happen. Wareham is the group’s cruise director — moderating morning strategy meetings, writing memos, getting everyone to the right room at the right time, handling the press, and sending tweets from the @BanKillerRobots account.

This year was the big one. The CCW was going to decide whether to go to the next level, to establish a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE), which would then decide whether or not to draft a treaty. If they didn’t move forward, the campaign was threatening to take the process “outside”— to another forum, like the UN Human Rights Council or an opt-in treaty written elsewhere. “Who gets an opportunity to work to try and prevent a disaster from happening before it happens? Because we can all see where this is going,” Wareham told me. “I know that this is a finite campaign — the world’s going to change, very quickly, very soon, and we need to be ready for that.”

That morning, countries delivered statements on their positions. Algeria and Costa Rica announced their support for a ban. Wareham excitedly added them to what she and other campaigners refer to as “The List,” which includes Pakistan, Egypt, Cuba, Ecuador, Bolivia, Ghana, Palestine, Zimbabwe, and the Holy See — countries that probably don’t have the technology to develop LAWS to begin with. All eyes were on Russia, which had given a vague statement suggesting they weren’t interested. “They always leave us guessing,” Wareham told me when we broke for lunch, reminding me only one country needs to disagree to stall consensus. The cafe outside the assembly room looked out on the UN’s verdant grounds. You could see placid Lake Geneva and the Alps in the distance.

In the afternoon, country delegates settled into their seats to take notes or doze with their eyes open as experts flashed presentation slides. The two back rows were filled with civil society, many of whom were part of the campaign. During the Q&A, the representative from China, who is known for being somewhat of an oratorical wildcard, went on a lengthy ramble about artificial intelligence. Midway through, the room erupted in nervous laughter and Erin Hunt, program coordinator from Mines Action Canada, fired off a tweet: “And now the panel was asked if they are smarter than Stephen Hawking. Quite the afternoon at #CCWUN.” (Over the next five days, Hunt would begin illustrating her tweets with GIFs of eye rolls, prancing puppies, and facepalms.)

A few seats away, Noel Sharkey, emeritus professor of robotics and artificial intelligence at Sheffield University in the UK, fidgeted waiting for his turn at the microphone. The founder of ICRAC, the International Committee for Robot Arms Control (pronounced eye-crack), plays the part of the campaign’s brilliant, absent-minded professor. With a bushy long white ponytail, he dresses in all black and is perpetually late or misplacing a crucial item — his cell phone or his jacket.

In the row over, Jody Williams, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 for her work banning landmines, barely suppressed her irritation. Williams is the campaign’s straight shooter — her favorite story is one in which she grabbed an American colonel around the throat for talking bullshit during a landmine cocktail reception. “If everyone spoke like I do, it would end up having a fist fight,” she said. Even the usually tactful Wareham stopped tweeting. “I didn’t want to get too rude or angry. I don’t think that helps especially when half the diplomats in that room are following the Twitter account,” she explained later and laughed.

But passionate as they all were, could this group of devotees change the course of humanity? Or was this like the campaign against climate change — just sit back and watch the water levels rise while shaking your head in dismay? How do you take on a revolution in warfare? Why would any country actually ban a weapon they are convinced can win them a war?

And maybe most urgently: With so many things plainly in front of us to be fearful of, how do you convince the world — quickly, because these things are already here — to be extra afraid of something we can&039;t see for ourselves, all the while knowing that if you fail, machines could kill us all?

Jody Williams (left), a Nobel Peace Laureate, and Professor Noel Sharkey, chair of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, pose with a robot as they call for a ban on fully autonomous weapons, in Parliament Square on April 23, 2013, in London, England.

Oli Scarff / Getty Images

One of the very real problems with attempting to preemptively ban LAWS is that they kind of already exist. Many countries have defensive systems with autonomous modes that can select and attack targets without human intervention — they recognize incoming fire and act to neutralize it. In most cases, humans can override the system, but they are designed for situations where things are happening too quickly for a human to actually veto the machine. The US has the Patriot air defense system to shoot down incoming missiles, aircraft, or drones, as well as the Aegis, the Navy’s own anti-missile system on the high seas.

Members of the campaign told me they do not have a problem with defensive weapons. The issue is offensive systems in part because they may target people — but the distinction is murky. For example, there’s South Korea’s SGR-A1, an autonomous stationary robot set up along the border of the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea that can kill those attempting to flee. The black swiveling box is armed with a 5.56-millimeter machine gun and 40-millimeter grenade launcher. South Korea says the robot sends the signal back to the operator to fire, so there is a person behind every decision to use force, but there are many reports the robot has an automatic mode. Which mode is on at any given time? Who knows.

Meanwhile, offensive systems already exist, too: Take Israel’s Harpy and second-generation Harop, which enter an area, hunt for enemy radar, and kamikaze into it, regardless of where they are set up. The Harpy is fully autonomous; the Harop has a human on the loop mode. The campaign refers to these as “precursor weapons,” but that distinction is hazy on purpose — countries like the US didn’t want to risk even mentioning existing technology (drones), so in order to have a conversation at the UN, everything that is already on the ground doesn’t count.

Militaries want LAWS for a variety of reasons — they&039;re cheaper than training personnel. There’s the added benefit of force multiplication and projection. Without humans, weapons can be sent to more dangerous areas without considering human-operator casualties. Autonomous target selection allows for faster engagement and the weapon can go where the enemy can jam communications systems.

Israel openly intends to move toward full autonomy as quickly as possible. Russia and China have also expressed little interest in a ban. The US is only a little less blunt. In 2012, the Department of Defense issued Directive 3000.09, which says that LAWS will be designed to allow commanders and operators to exercise “appropriate levels of human judgment over the use of force.” What “appropriate” really means, how much judgment, and in which part of the operation, the US has not defined.

In January 2015, the DoD announced the Third Offset strategy. Since everyone has nuclear weapons and long-range precision weapons, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work suggested emphasizing technology was the only way to keep America safe. With the DoD’s blessing, the US military is racing ahead. Defense contractor Northrop Grumman’s X-47B is the first autonomous carrier-based, fighter-sized aircraft. Currently in demos, it looks like something from Independence Day: The curved, grey winged pod takes off from a carrier ship, flies a preprogrammed mission, and returns. Last year, the X-47B autonomously refueled in the air. In theory, that means except for maintenance, an X-47B executing missions would never have to land.

At an event at the Atlantic Council in May, Work said the US wasn’t developing the Terminator. “I think more in terms of Iron Man — the ability of a machine to assist a human, where the human is still in control in all matters, but the machine makes the human much more powerful and much more capable,” he said. This is called centaur fighting or human–machine teaming.

Among the lauded new technologies is swarms — weapons moving in large formations with one controller somewhere far away on the ground clicking computer keys. Think hundreds of small drones moving as one, like a lethal flock of birds that would put Hitchcock’s to shame, or an armada of ships. The weapons communicate with each other to accomplish the mission, in what is called collaborative autonomy. This is already happening — two years ago, a small fleet of ships sailed down the James River. In July, the Office of Naval Research tested 30 drones flying together off a small ship at sea that were able to break out of formation, perform a mission, and then regroup.

Quelle: <a href="How To Save Mankind From The New Breed Of Killer Robots“>BuzzFeed