Adam Mosseri onstage at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.

Craig Silverman

PERUGIA, Italy — “This actually makes me a little bit uncomfortable,” said Adam Mosseri, Facebook’s VP of News Feed, to a packed room of journalists and members of the public on Friday.

Mosseri was there to explain how Facebook News Feed works, and to share new projects related to news discovery and “integrity” the company is working on for its close to 2 billion global users. What made Mosseri uncomfortable, he said, was giving a sneak peek at new products they were testing — products that might never be fully rolled out.

“We don’t generally share much about what we’re doing before we do it,” he said.

Those in the audience could be forgiven for thinking Mosseri was talking less about his product roadmap and more about being in that room at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy. Almost exactly two years before, Andy Mitchell, the company’s director of global media partnerships, gave a keynote that in the ensuing time has become viewed by attendees of the IJF as something of a PR disaster.

Mitchell's prepared remarks back in 2015 weren&039;t the issue. It was his handling of questions about difficult topics such as censorship and Facebook&039;s responsibilities as a platform that stuck with people.

“Do you think that you are accountable for the quality and integrity of your decisions to your community of users?” asked George Brock of City, University of London, to applause from the audience.

“We have to create a great experience for people on Facebook, and like I said earlier Facebook should be a complimentary news source,” Mitchell replied.

Brock tried to yell out a follow up but time was up. People left feeling Facebook was doing everything it could to avoid acknowledging its massive influence over the digital news ecosystem.

Brock wrote afterward that Mitchell&039;s answers were “condescending and dishonest.” Press critic and professor Jay Rosen said Mitchell and Facebook were “treating us like children at a Passover seder who don’t know enough to ask a good question.”

Two years later, people still remember.

“It was horrible,” said a European journalist seated next to me at Mosseri’s talk this year. She saw Mitchell and wanted to see if Mosseri would be any different. “If [Mitchell] had stayed any longer I had the feeling people would storm the stage. He tried to downplay Facebook’s role and people felt bullshitted.”

Up until very recently, Facebook was known for keeping its product roadmaps, checkbook, and public comments close to its chest. The company is also sometimes seen as avoiding panels and public events where its people might face tough questions about the power it wields over digital news. On top of that, for a long time it steadfastly clung to the idea that it&039;s purely a technology company.

But in the months since it was rocked by criticism for the spread of misinformation on its platform during the US election, Facebook began changing how it engages with the news industry, and how it talks about its role providing information to people. The company recently announced it’s a key funder of a new $14 million initiative about “news integrity.” That followed a January launch of the Facebook Journalism Project.

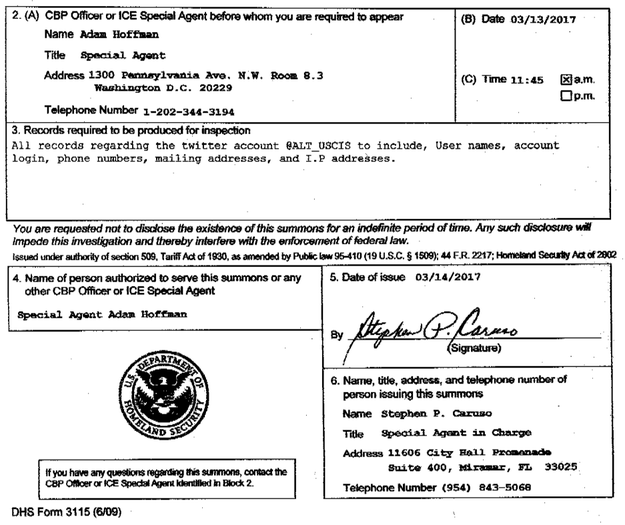

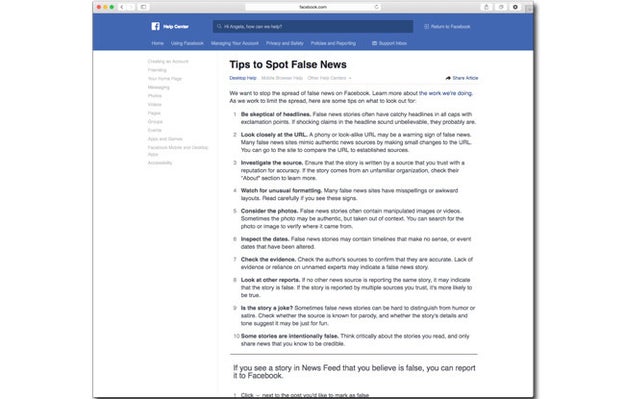

At this year&039;s festival it launched a new program to educate users in 14 countries about how to spot “false news.” This is the latest effort around misinformation, which also includes a recently rolled-out partnership with third-party fact-checking groups, among other initiatives.

Facebook is now a company where CEO Mark Zuckerberg writes a 6,000-word essay on his view of community, and where he now acknowledges that Facebook is a “new kind of platform” that brings with it “a new kind of responsibility.” (“It could have been shorter,” Mosseri joked about Zuckerberg’s manifesto during his talk.) Zuckerberg’s Facebook profile also recently featured a photo of him and his wife reading a local newspaper during a visit to Alabama.

View Video ›

facebook.com

“It seems like a good time to say thank you to all the journalists around the world who work tirelessly and sometimes put their lives in danger to surface the truth,” he wrote.

Running through all of this is a new, humble tone that Mosseri put on display right from the start.

“It’s a difficult time to be in the news industry,” he said. “We’re trying to figure out how we might be better partners and we haven’t always been the best at communicating, which is really in my opinion a problem with News Feed.”

Mosseri’s keynote was part of a full-court press at IJF. The company sent what festival organizer Chris Potter told BuzzFeed News was roughly 30 employees to give workshops and to sit on panels about contentious topics such as fake news and online misinformation. A phalanx of PR staff set up private meetings with Mosseri and select journalists.

“A cynic would say, ‘Oh it’s PR and corporate marketing,’” Potter said in an interview. “That’s one point of view, and it’s reasonable given past experience. But I think there’s a bit more to it than that.”

He said Facebook reached out to him last year to say it wanted to play a big role in this year’s festival. “There’s been no imposition, no arrogance, no kind of heavy-handedness” in his dealings with the company, according to Potter.

“Whether you believe it or not, whether it’s marketing or truth, at least there is an effort being made, it seems to me, to reach out and say, ‘Yeah, this is a collective problem,’” he said.

That’s one of the core messages from the new, humble Facebook.

“Issues like false news are bigger than Facebook,” Mosseri said onstage. “They require industry-wide solutions and there are no silver bullets.”

Craig Silverman

The company now freely talks about its responsibility to users and to the news industry.

“We are a very large platform and that comes with very serious responsibilities, and one of which is to make sure we’re doing our part to support informed communities,” Mosseri said.

“I’ve noticed this time around the whole Facebook team, not just Adam Mosseri, they’re all singing from the same hymn sheet,” Potter said. “They’ve certainly gone through some rigorous staff training to make sure they know how to respond to particular questions. There’s no “How dare you’ kind of response [from them].”

Another line delivered consistently by Facebook executives is that the company doesn&039;t want to “become the arbiters of truth” when it comes to content. It’s attempting to walk the line between reducing the spread of misinformation on its platform while simultaneously sidestepping concerns about censorship and political bias.

Jeff Jarvis, a professor at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism, is one of the people who brought Facebook to the table to fund the News Integrity Initiative, which his school will administer. He sees that funding, which he stresses comes with no restrictions on how it will be spent, as part of a bigger change at Facebook. Jarvis said the shift may also have something to do with the other big platform the news industry is always obsessing over: Google.

“What we always saw was Google was ahead in the public-facing end of news and not so much on the product side, and Facebook was ahead on the product side but not so much on the public-facing voice,” Jarvis said. “And now I think that Facebook is trying to catch up on the public-facing voice very quickly.”

Google has spent, or pledged, hundreds of millions of dollars in the past few years on initiatives related to the news industry. It’s also been present on panels at conferences. This year at the festival Facebook and Google held receptions in the exact same room, with the exact same food and drink on offer, one day after each other.

This is just the start of Facebook’s new charm and chequebook offensive for the news industry. So while Mosseri and other executives are ready to talk about its responsibility to the news industry and how to stop false content from going viral, other questions go unanswered.

After his keynote, Mosseri was asked to share data about the collaboration with third-party fact-checkers to label false content. He responded but didn&039;t share any data. Partners involved in the program have told BuzzFeed News they have yet to see much in the way of data from the company, and the head of the International Fact-Checking Network also tweeted about the lack of data so far.

Jeff Jarvis was onstage with Mosseri to moderate a Q&A after the keynote. After the fact-checking question he walked over to George Brock, the journalism professor whose question to Andy Mitchell two years ago stuck in the minds of so many. Jarvis told BuzzFeed News he told Brock ahead of time to be ready with a question, as a way to connect the dots back to what happened the last time Facebook was on this stage.

But rather than pushing Facebook to acknowledge its role and responsibility to news and the information ecosystem, Brock urged Mosseri to think bigger than journalism.

“You’re the largest one-stop shop for information on the planet and I think you should stop worrying quite so much about problem-solving for journalism,” Brock said. “What actually you’re doing is you have a potential role in a reconstruction effort in civil society … . You could go a lot further. I want to encourage you to go there. Will you go?”

The crowd began to applaud and a smile spread across Mosseri’s face.

“We’re certainly going to try,” he said.

Quelle: <a href="A More Humble Facebook Is Deploying Charm And Its Checkbook To Win Over Critics“>BuzzFeed