Nurhaida Sirait, a grandmother that speaks the native Batak language and uses Facebook on her smartphone to connect to friends and family, poses for a portrait.

Andri Tambunan for BuzzFeed News

JAKARTA, Indonesia — When Nurhaida Sirait-Go curses, she curses in her mother tongue.

The 60-year-old grandmother does everything emphatically, and Bahasa, the official language of Indonesia, just doesn’t allow for the same fury of swearing as Bakat, the language that Sirait-Go grew up speaking on the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

“On Facebook, on Whatsapp, they speak only Bahasa. So I can’t speak the way I want,” said Sirait-Go, who giggles uncontrollably and covers her mouth with both hands when asked to repeat one of her favorite curse words in Bakat. “I can’t, I can’t! People don’t use these words anymore. … They aren’t on the internet so they don’t exist.”

Bakat is one of over 700 languages spoken in Indonesia. But only one language, Bahasa, is currently taught by public schools and widely-used online. For language preservationists, it’s just one more example of how the internet’s growing global influence is leaving some languages in the dust. Linguists warn that 90% of the world's approximately 7,000 languages will become extinct in the next 100 years. Or, as one prominent group of linguists ominously put it, every 14 days another language goes extinct.

The trend that started hundreds of years ago, as the idea of a “nation state” took hold globally, with governments realizing that a standardized language would help them stand out as a nation state and solidify an identity inside their borders. That process, which sped up as languages like French and English became dominant languages among traders and then diplomats, went into overdrive as the internet’s sweeping reach has encouraged users to engage in the language with the highest common denominator.

Linne Ha, a program manager at Google who focuses on low resource languages, estimates that there are at least thirty languages with one million speakers each that are currently not supported online — and there are many many more with less than a million speakers. If you were to imagine all those people as one group, it would be a country roughly the size of the United States which couldn’t type online, let alone use the text-to-speech function that make things like Google Maps reading you your directions as you drive possible.

“We are biased because all of the equipment is designed for us,” Ha told BuzzFeed News. “The first thing, the default, is an English language keyboard, but what if your language doesn’t use those characters, or what if your language is only spoken, but not written?”

According to the UN, roughly 500 languages are used online, though popular sites like Facebook and Twitter support just 80 and 28 respectively. Those sites also display their domain names, or URLs, in Latin letters — for millions of people around the world, the letters www.facebook.com are nothing more than a string of shapes to be remembered or copy/pasted into an address bar. The internet, largely in English, does not feel as though it was built to speak their language.

Facebook profile page of Nurhaida Sirait, a grandmother that speaks the native Batak language and uses Facebook on her smartphone to connect to friends and family.

Andri Tambunan for BuzzFeed News

Ha worries about whether or not the internet is harming the world’s diversity of languages. She has been working Google for ten years, the last two of which she has had the unique job title of “voice hunter” for Google’s Project Unison. Getting a language online means everything from developing a font, which can cost upwards of $30,000 to design and code, to recording and creating voice capabilities for the language that power programs like Google Maps. It’s the voice part that Ha is focused on. As many parts of the world come online which use spoken, rather than written languages, it’s become more important than ever to be able to use speak functions on the internet.

“In much of the world the phone, specifically using your voice commands on the phone, that is the standard way to communicate,” said Ha. “These are places where there is more of an oral tradition than a written one.”

The Wu language, spoken by roughly 80 million people in the Shanghai region of China, is a prime example. Spoken Wu has many characters that cannot be written with standard Chinese characters, and the language is rarely written as schools only teach students to read and write in Mandarin. For Wu speakers to be fully immersed in using and conversing on the internet, a function must be created for them to be able to speak, and hear, their language online.

Others, she said, were simply not easy to adapt to the average keyboard. The Khmer language, which is spoken by 18 million people in Cambodia, includes 33 consonants, 23 vowels, and 12 independent vowels.

“On the type of keyboards you get on your phone they have to click and go through three sets of keyboards to type in one word. It’s cumbersome,” said Ha. The solution, Ha says, is what’s called a “transliteration keyboard,” where spoken words take the place of a traditional keyboard.

“Previously, in order to create a voice, a speech synthesis voice, you would need to record really good acoustic data, and have all the different sounds of a language,” said Ha. That required bringing in a “voice talent”, or a local with what Ha calls the perfect voice, a voice that any native person of that language would find pleasant and easy to understand. They were joined by a project manager and 3-4 people in a recording studio. The process, Ha said, would take six months or more to record all the necessary sounds which make up a language. “It was really really expensive.”

Ha, however, helped develop a way to use machine learning, otherwise known as artificial intelligence (AI), to bring a new language online in a matter of days. The new process takes advantage of what’s known as a “neural network,” a type of AI that tries to emulate the way a human brain works. Like a toddler learning which foods it likes and doesn’t like, the system works through trial and error, rewriting itself through patterns in the data it is given.

Ha said she got the idea for how to streamline the process one day while watching Saturday Night Live. “When I was watching SNL I saw all these comedians mimicking politicians. I thought that was interesting, one person pretending to be different people,” said Ha. A handful of voices, she realized, when sent through a system capable of analyzing them and recognizing patterns, could be enough to create a complete language database.

She began with a team of 50 Bengali speakers in Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. Ha’s team built a web app which could run on a ventless laptop (fans would distort the recording) and recorded the voices of the Bengali Google employees. She then ran a survey asking the group which voice they liked the best; once she had a reference voice, she then looked for voices that had a similar cadence.

“These volunteers, we didn’t want them to get tired. We had them speak in 45 minute increments, roughly 145 sentences. So in three days we got 2000 sentences,” said Ha. The system then built patterns out of the words and expanded the vocabulary. “With that we were able to build a model. It took three days to build a book of the Bengali voice.”

“The voice we created is a blend of seven voices. It’s like a choir”

Ha then built a portable recording booth, small enough to fit in a carry on, which she has now used to travel around the world. So far, she’s used it to bring three new languages online — Bengali, Khmer, and Sinhala — in the course of the last year.

“The voice we created is a blend of seven voices. It’s like a choir,” said Ha, reflecting on the finished voices they have presented to the public. Earlier this year she visited Indonesia, where she partnered with a local university and is working on bringing two more languages spoken in Indonesia, Javanese and Sundanese, online.

In Jakarta, Sirait-Go was “thrilled” to hear that Google was working to bring more languages online, though she was less impressed to hear their pilot program in that country had been with Javanese, rather than her native tongue of Batak.

“It would be much better for everyone if they could speak in Batak, they could express themselves better,” said Sirait-Go.

When asked about what she communicates online, she runs to the next room to bring back a pristine Samsung Galaxy phone her daughter bought her in May of this year. She keeps it in a separate room, on a shelf of its own, whenever she’s not using it.

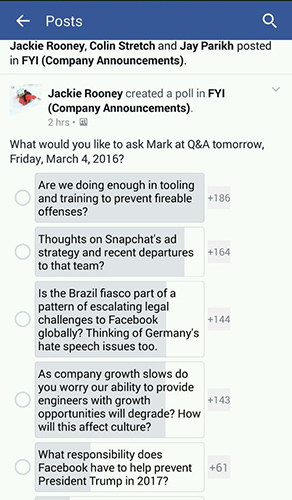

“My kids tell me to use the internet, to not be old fashioned, but I don’t know what to do there,” said Sirait-Go, who recently welcomed her fifth grandchild. She opens her phone to show her 168 friends on Facebook (she has an additional 55 friend requests but isn’t sure how to answer them). Her Facebook page is largely made up of photos of Sumatra, particularly of Lake Toba, where she grew up.

“I have a video of the lake too&033; Someone is speaking in the video in Batak and that makes me happy to hear,” said Sirait-Go. Her daughters and grandchildren, she said, only use Batak when they are making fun of her.

“I don’t think my grandchildren or great grandchildren will learn Batak and that makes me sad,” she said. “If they cannot speak it on the internet they will not learn it.”

Quelle: <a href="This Is How Google Wants To Make The Internet Speak Everyone’s Language“>BuzzFeed